_Music and writing are not mere preoccupational art forms to me.

They are my modes of existence. My means of becoming. They enable me to

deal with the very act of existence. They remind

me who I have to be to evolve.

Plays

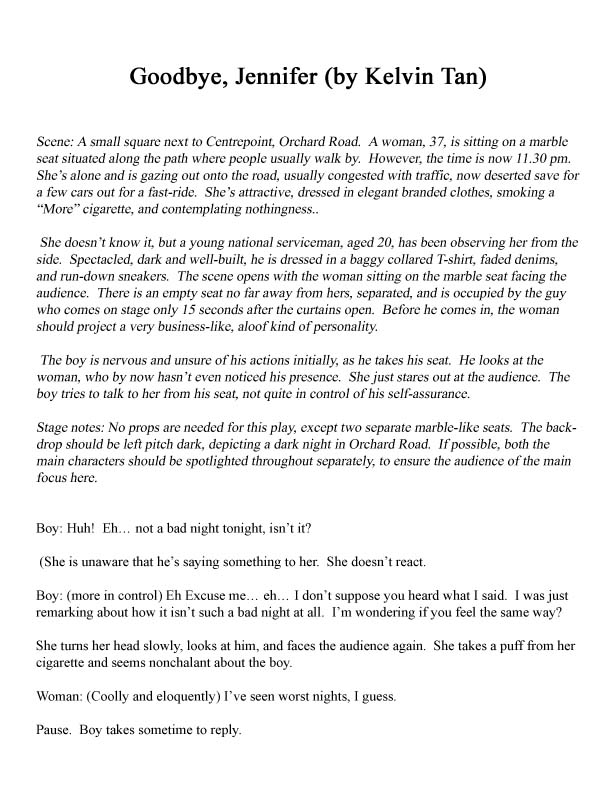

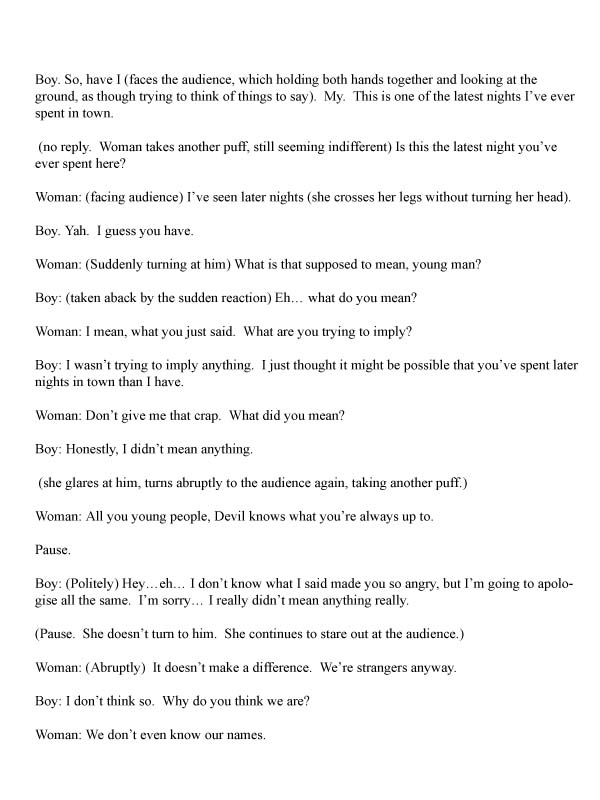

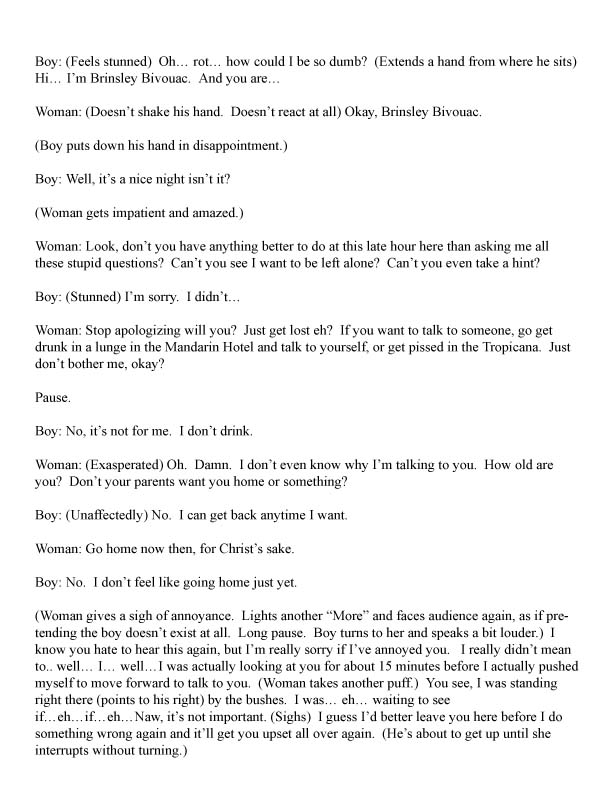

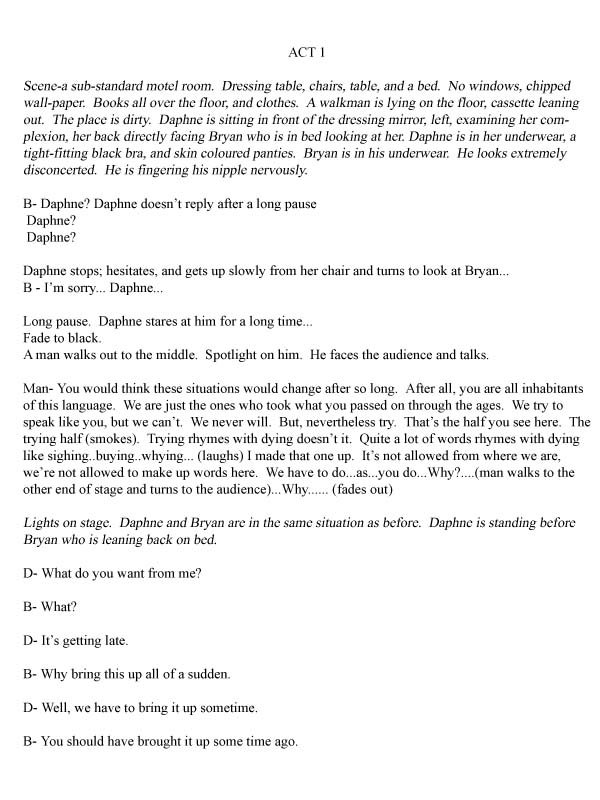

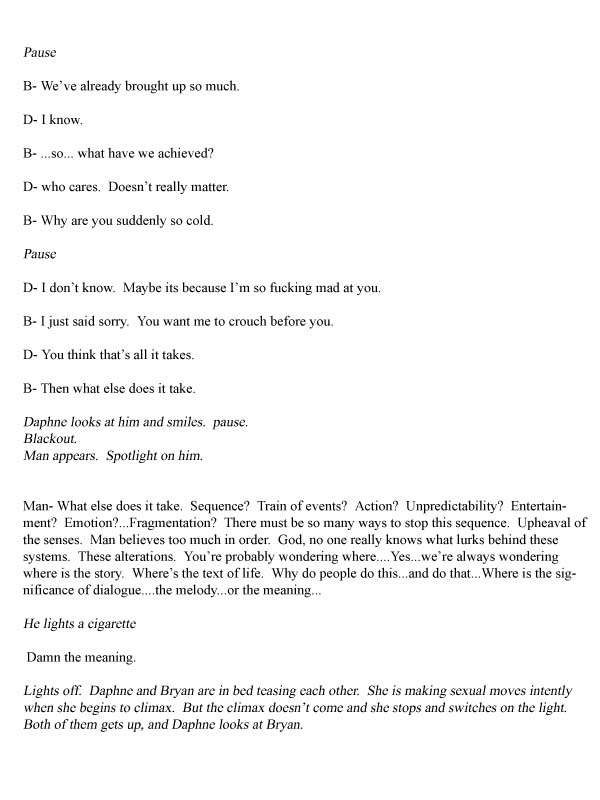

Goodbye Jennifer, 1987/88.

Excerpts from Goodbye Jennifer:

Tramps like us, 1989

(staged the play as the first project of Aporia Society in November 1997)

image take from http://aporiasociety.org/theatre.html

"Tramps Like Us" was written in 1989 by Kelvin Tan Yew Leong, it was apparently awarded the joint second prize at the National University of Singapore Drama Competition, the first prize was awarded to a forgettable effort by a mediocre local playwright. It was also staged at the Lecture Theatre 13 (where most performances were staged before the horrible new Uinversity Cultural Center was built). The remarkable thing about Tramps was that it identified a lost period that most of us have forgotten about, or have never even heard of. This was the period when many were trying to make music and art in the eighties in Singapore. The general attitude towards the arts and music was very different at that time and is reflected in the play.

Yet the remarkable thing about this work is that what it said about Singapore society, art, music is still true. We still to a large extent do not accept or embrace works by Singaporean artists, musicians, unless it's packaged with a "made it overseas" label. I think this has always been due to biasness of Singaporeans against their own sons and daughters and the general atmosphere where anything remotely individual is regularly discouraged.

Tramps is the story of a young musician and his writer friend who try to make their way in the cultural dessert that was Singapore and still continues to be. In this particular production, I had improvised elements and expanded the dialogue between the two protagonists as well as adding in the character of the musician's mother and a annoynmous Chinese man who recited the Chinese classic the "Three Character Classic" backwards at various moments in the play. This person represented the cultural mix of Singaporeans, very much torn between the east and the west.

(the above is an article written by director Wong Kwang Han, and is taken from his website www.aporiasociety.org. To read the full article, and a review, go HERE.)

Yet the remarkable thing about this work is that what it said about Singapore society, art, music is still true. We still to a large extent do not accept or embrace works by Singaporean artists, musicians, unless it's packaged with a "made it overseas" label. I think this has always been due to biasness of Singaporeans against their own sons and daughters and the general atmosphere where anything remotely individual is regularly discouraged.

Tramps is the story of a young musician and his writer friend who try to make their way in the cultural dessert that was Singapore and still continues to be. In this particular production, I had improvised elements and expanded the dialogue between the two protagonists as well as adding in the character of the musician's mother and a annoynmous Chinese man who recited the Chinese classic the "Three Character Classic" backwards at various moments in the play. This person represented the cultural mix of Singaporeans, very much torn between the east and the west.

(the above is an article written by director Wong Kwang Han, and is taken from his website www.aporiasociety.org. To read the full article, and a review, go HERE.)

Flights Through Darkness, 1994/95.

_Excerpts from Flights Through Darkness:

Essays

The Protection Paintings, 2008

- Jeremy Sharma's harbour from the vulnerabilities of be-coming

12.2.09

"Accept that I can plan nothing.

Any consideration that I make about the 'construction' of a picture is false and if the execution is successful then it is only because I partially destroy it or because it works anyway, because it is not disturbing and looks as though it is not planned.

Accepting this is often intolerable often intolerable and also impossible, because as a thinking planning human being it humiliates me to find that I am powerless to that extent, making me doubt my competence and any constructive ability. The only consolation is that I can tell myself that despite all this I made the pictures even when they take the law into their own hands, do what they like with me although I don't want them to, and simply come into being somehow. Because anyway I am the one who has to decide what they should ultimately look like (the making of pictures consists of a large number of yes and no decisions and a yes decision at the end). Seen like this the whole thing seems quite natural to me though, or better nature-like, living, in compassion with the social sphere as well. “

Gerhard Richter

Entries from the artist's private journal,

Translated and published for the first time on the occasion of an exhibition of his work at the Tate Gallery, London 30 October 1991-12 January 1992, and reproduced in the catalogue, Gerhard Richter, London (Tate Gallery), 1991, pp. 123-4, from which the present text is taken.

An artist is his own worst enemy, and yet his own best friend.

“Man . . . the human person . . . the tree individual . . . the I . . . at once torturer and victim . . . at once hunter and prey . . . man - and man alone - reduced to a thread – in the dilapidating and misery of the world – who searches for himself – starting from nothing . . .”

Francis Ponge (1899 – 1988)

Reflections on the Statuettes, Figures & Paintings of Albero Giacometti

Originally published in Cahiers d'Art, Paris , 1951.

And yet, it is though this tension of enemy/friend, torturer/victim, hunter/prey that the most vital works are being made. Vital, in that they push for a sense of questioning & probing not realized before, in the approach and treatment of the work. And yet, the artist can't ‘consider' too much about the work his about to make. It's as if ‘considering' results in a ‘falsity' that is potentially there already in the making. All works of Art have a foundation of imagining that has its roots in some notion of falseness. The trick is to have an imaginative ‘falseness' and not one borne out of contrived inhibitions.

Yet, in the end, the artist has to ‘decide' what does the deciding involve? How to alter, how to re-define? Or how to destroy? How to re-create. No matter what stance he takes, it will have absolutely nothing to do with how an audience will appreciate it or recreate it with their senses, Somehow, the artist has to master the courage to slip between the unknowing and instinct, to push the creating that excludes an audience, simply because he's own be-coming is far greater & more important than what happens in the “social sphere.”

There-in lies the challenge for an Artist who needs to preserve his own purity for the sake of his own accountability to his Art. There-in lies the vulnerabilities. A power-lessness to change anything in the world, but the power to refuse to compromise to that power-lessness. Yet, vulnerability is so important to how a work is made. For it is in vulnerability and accepting that we ‘can plan nothing', that the work creates herself in a realm of pure unadulterated honest spontaneity.

In the ‘Protection' Paintings, Jeremy Sharma's attempts to push the vulnerabilities to their purest ends are very genuine. In his past works, Sharma had dealt a lot with markings, text and abstract formulations as foundations that led to a larger plane of complex thought-maps weaved into the forms.

It is evident in the new works, that he has tried to combine all the conceptual aspects of his past works into it, and the results are very intriguing indeed. Indeed the whole idea of superscriptions is very apt. It is fascinating to see the layer of image, text and vague referentials collide, contrast, or compliment on top or with one another. In super-scribing, Sharma is also metaphorically creating layers of sub-textual data that seem to come close to saying something and yet stop short. But as a whole, they distort the messages and perhaps that is the point. Its all about the multi-layered metaphors that say something, only if an audience is willing to make that effort to connect to them.

Why Protection? Perhaps the connection it has to vulnerabilities. The painter, in his darkest moments, fritter from one thought to another without knowing what would be the final ‘decision'. He is left to, through his work, expose his own emotional and spiritual wounds, and yet not over-expose them to contriteness. The wounds have to be connected to a deeper realization that they can be healed by the ‘work.'

In this way, the artist's own personal healing is via the work, that he cannot create until he is totally painfully honest about his own turmoil and to convert that turmoil into an aesthetic vulnerability. In this sense, vulnerability is Art leads to a certain protection. A process that involves, as Richter has noted, ‘humiliation' and ‘doubt' about one's ‘competence' and ‘constructive ability'.

This is a process that Sharma has very obviously been willing to do, and that is why his new work, leaves you wondering where the foundations of the work are. Which is the point – Sharma's aesthetic vulnerabilities has this need to transcend above the genres and let instinct take over to create an inner, emotional landscape expanded onto the canvas, free of contrite artistic speculations.

Whether they are the multitude of mysterious-looking faces or the wide canvas of rampant colour & shapes rich in images of hints of notions of ‘safety' or ‘protection', Sharma imbues in them an astonishing array of unknowable shapes and figures that hint, but never define it for us. He treats them in an arresting scourge of colour. Scourge, in that they slash into your mind but never define themselves. They are works that questions not just our consciousness, but the consciousness of what Art is, & can do.

“4 The creation of a work of art cannot be reduced to formulae, nor to some construction of more or less decorative forms, rather it supposes a presence, it is an adventure in which a man commits himself to struggle with the fundamental forces of nature.

To see this through to the bitter end, some of us today risk our necks, we turn our backs on vain quarrels about doctrine, resolutely committing ourselves to those directions which fashion and the public can barely follow.”

Jean-Michael Atlan (1913 – 1960)

‘Abstraction and Adventure in contemporary Art'

First published in Cobra in April 1950.

Reprinted in the catalogue of the exhibition

‘Paris-Paris: Creations en France 1937 – 1957' 1981

It seems that Atlan's manifesto in 1950 seems even more appropriate and important now. Painting defies, in that its struggle is to attempt to overturn complacent ideas about society that technology cannot do, simply in its very human-ness. In that sense, Abstraction in painting is even more important, in that it subverts everything adigitalised, skills-oriented public is accustomed too. The connection between a human hand to a fresh canvas have never been more mysterious than now.

Artists like Jeremy Sharma, especially in the ‘Protection' Paintings, belong to that rare breed of artists, who are not ‘reduced to formulae', who are committed to the ‘struggle with the fundamental forces of nature' and who will ‘risk their necks', “turn their backs on vain quarrels about doctrine, resolutely committing ourselves to those directions which fashion and the public can barely follow.”

The integrity, sincerity, dignity and the unrelenting honesty & purity of the ‘Protection' Paintings speak for themselves. It is only our loss, if we can barely follow.

12.2.09

"Accept that I can plan nothing.

Any consideration that I make about the 'construction' of a picture is false and if the execution is successful then it is only because I partially destroy it or because it works anyway, because it is not disturbing and looks as though it is not planned.

Accepting this is often intolerable often intolerable and also impossible, because as a thinking planning human being it humiliates me to find that I am powerless to that extent, making me doubt my competence and any constructive ability. The only consolation is that I can tell myself that despite all this I made the pictures even when they take the law into their own hands, do what they like with me although I don't want them to, and simply come into being somehow. Because anyway I am the one who has to decide what they should ultimately look like (the making of pictures consists of a large number of yes and no decisions and a yes decision at the end). Seen like this the whole thing seems quite natural to me though, or better nature-like, living, in compassion with the social sphere as well. “

Gerhard Richter

Entries from the artist's private journal,

Translated and published for the first time on the occasion of an exhibition of his work at the Tate Gallery, London 30 October 1991-12 January 1992, and reproduced in the catalogue, Gerhard Richter, London (Tate Gallery), 1991, pp. 123-4, from which the present text is taken.

An artist is his own worst enemy, and yet his own best friend.

“Man . . . the human person . . . the tree individual . . . the I . . . at once torturer and victim . . . at once hunter and prey . . . man - and man alone - reduced to a thread – in the dilapidating and misery of the world – who searches for himself – starting from nothing . . .”

Francis Ponge (1899 – 1988)

Reflections on the Statuettes, Figures & Paintings of Albero Giacometti

Originally published in Cahiers d'Art, Paris , 1951.

And yet, it is though this tension of enemy/friend, torturer/victim, hunter/prey that the most vital works are being made. Vital, in that they push for a sense of questioning & probing not realized before, in the approach and treatment of the work. And yet, the artist can't ‘consider' too much about the work his about to make. It's as if ‘considering' results in a ‘falsity' that is potentially there already in the making. All works of Art have a foundation of imagining that has its roots in some notion of falseness. The trick is to have an imaginative ‘falseness' and not one borne out of contrived inhibitions.

Yet, in the end, the artist has to ‘decide' what does the deciding involve? How to alter, how to re-define? Or how to destroy? How to re-create. No matter what stance he takes, it will have absolutely nothing to do with how an audience will appreciate it or recreate it with their senses, Somehow, the artist has to master the courage to slip between the unknowing and instinct, to push the creating that excludes an audience, simply because he's own be-coming is far greater & more important than what happens in the “social sphere.”

There-in lies the challenge for an Artist who needs to preserve his own purity for the sake of his own accountability to his Art. There-in lies the vulnerabilities. A power-lessness to change anything in the world, but the power to refuse to compromise to that power-lessness. Yet, vulnerability is so important to how a work is made. For it is in vulnerability and accepting that we ‘can plan nothing', that the work creates herself in a realm of pure unadulterated honest spontaneity.

In the ‘Protection' Paintings, Jeremy Sharma's attempts to push the vulnerabilities to their purest ends are very genuine. In his past works, Sharma had dealt a lot with markings, text and abstract formulations as foundations that led to a larger plane of complex thought-maps weaved into the forms.

It is evident in the new works, that he has tried to combine all the conceptual aspects of his past works into it, and the results are very intriguing indeed. Indeed the whole idea of superscriptions is very apt. It is fascinating to see the layer of image, text and vague referentials collide, contrast, or compliment on top or with one another. In super-scribing, Sharma is also metaphorically creating layers of sub-textual data that seem to come close to saying something and yet stop short. But as a whole, they distort the messages and perhaps that is the point. Its all about the multi-layered metaphors that say something, only if an audience is willing to make that effort to connect to them.

Why Protection? Perhaps the connection it has to vulnerabilities. The painter, in his darkest moments, fritter from one thought to another without knowing what would be the final ‘decision'. He is left to, through his work, expose his own emotional and spiritual wounds, and yet not over-expose them to contriteness. The wounds have to be connected to a deeper realization that they can be healed by the ‘work.'

In this way, the artist's own personal healing is via the work, that he cannot create until he is totally painfully honest about his own turmoil and to convert that turmoil into an aesthetic vulnerability. In this sense, vulnerability is Art leads to a certain protection. A process that involves, as Richter has noted, ‘humiliation' and ‘doubt' about one's ‘competence' and ‘constructive ability'.

This is a process that Sharma has very obviously been willing to do, and that is why his new work, leaves you wondering where the foundations of the work are. Which is the point – Sharma's aesthetic vulnerabilities has this need to transcend above the genres and let instinct take over to create an inner, emotional landscape expanded onto the canvas, free of contrite artistic speculations.

Whether they are the multitude of mysterious-looking faces or the wide canvas of rampant colour & shapes rich in images of hints of notions of ‘safety' or ‘protection', Sharma imbues in them an astonishing array of unknowable shapes and figures that hint, but never define it for us. He treats them in an arresting scourge of colour. Scourge, in that they slash into your mind but never define themselves. They are works that questions not just our consciousness, but the consciousness of what Art is, & can do.

“4 The creation of a work of art cannot be reduced to formulae, nor to some construction of more or less decorative forms, rather it supposes a presence, it is an adventure in which a man commits himself to struggle with the fundamental forces of nature.

To see this through to the bitter end, some of us today risk our necks, we turn our backs on vain quarrels about doctrine, resolutely committing ourselves to those directions which fashion and the public can barely follow.”

Jean-Michael Atlan (1913 – 1960)

‘Abstraction and Adventure in contemporary Art'

First published in Cobra in April 1950.

Reprinted in the catalogue of the exhibition

‘Paris-Paris: Creations en France 1937 – 1957' 1981

It seems that Atlan's manifesto in 1950 seems even more appropriate and important now. Painting defies, in that its struggle is to attempt to overturn complacent ideas about society that technology cannot do, simply in its very human-ness. In that sense, Abstraction in painting is even more important, in that it subverts everything adigitalised, skills-oriented public is accustomed too. The connection between a human hand to a fresh canvas have never been more mysterious than now.

Artists like Jeremy Sharma, especially in the ‘Protection' Paintings, belong to that rare breed of artists, who are not ‘reduced to formulae', who are committed to the ‘struggle with the fundamental forces of nature' and who will ‘risk their necks', “turn their backs on vain quarrels about doctrine, resolutely committing ourselves to those directions which fashion and the public can barely follow.”

The integrity, sincerity, dignity and the unrelenting honesty & purity of the ‘Protection' Paintings speak for themselves. It is only our loss, if we can barely follow.

The Aura of Becoming - Sia Joo Hiang's artistic questioning of the truth in painting.

_ Written for Joo's solo exhibition The Space Between The Punches in 2005

“A proposition is true by conforming to the unconcealed, to what is true. Propositional truth is always, and always exclusively, this correctness. The critical concepts of truth which, since Descartes, start out from truth as certainty, are merely variations of the definition of truth as correctness. The essence of truth which is familiar to us – correctness in representation – stands and falls with truth as unconcealment of beings.”[i]

If one stands in the gap of artistic questioning, the main question besides “what is true in Art?” would be “what is the truth in Art?” The storms of subjectivity flood such questionings, but more so, the complexities of Being. But what should always be apparent are the questionings, or the reflecting on these questions.

We often assume that Art conceals. We shun the obvious, disregard autobiographies, and proclaim that unmasking the masking is the key to great works of Art. What underlies Art is what makes the Truth deeper. We want gaps, not the obvious. We want “variations of the definition of truth of correctness.”

How important then, is the “unconcealment of Beings.” How should Art “unconceal?” These are age-old questions that will never be totally answered. Simply because human existence and the cosmos have always been more ‘projected’ and ‘concealed’ than ‘revealed’ to the world. This tension between concealment and unconcealment is, however, a very focal point of Artistic Truth.

In Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1573-1610) we see a classic example of that tension. The Saints and the Son of God are revealed in the magnitude. But the skepticism that is so prevalent beneath the revealing – the rebellious Christ, the cynical soldier, the truly vulnerable and confessional Apostle Peter in the midst of total despair. Caravaggio was unique, in that, he truly lived the Outside. As if he understood that standing on the fringes of the Outside was where the Truth was more illuminating.

Perhaps there’s a link.

“Truth establishes itself in the work. Truth essentially occurs only as the strife between clearing and concealing in the opposition of world and earth.”[ii]

What is this “strife?” What is to be ‘cleared’ or ‘concealed?’ In Caravaggio’s work, as in those of Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Eric Fischl, there is the strife between what one must strip to reveal and what one must conceal in order to provoke and reveal even deeper.

“Truth establishes itself in a being in such a way, indeed, that this being itself takes possession of the open region of truth. This occupying, however, can happen only if what is to be brought forth, the rift, entrusts itself to the self-secluding element that juts into the open region.”[iii]

“Self-secluding” is perhaps the most potent form of Truth-seeking in Art. The need to isolate, to avoid, and place oneself in a void of sometimes violent self-reflection is perhaps what binds the truth of the work to the viewer wanting the Truth in Art. Perhaps all we have are the experiences and the honesty that results in the work. Not to leave out the idealism and the courage to fail and to achieve the work.

In Sia Joo Hiang’s work, we are enthralled not just by the intensity of the work, but by the sheer exhaustive range of it. It is as though, different visual mediums are not enough to appease her restless search for what’s true. Her need to document her own personal “strife” and the “strife” of the work reveals to us the ultimate struggle of what to conceal and what not to. Or to totally expose a state of mind torn between chaos, complex peace and purity.

“…It says on one hand: art is the fixing in place of self-establishing truth in the figure. This happens in creation as the bringing forth of the unconcealment of beings. Setting-into-work, however, also means the bringing of work-being into movement and happening. This happens as preservation. Thus art is the creative preserving of truth in the work. Art then is a becoming and happening of truth. Does truth, then, arise out of nothing? It does indeed if by nothing we mean the sheer “not” of beings, and if we here think of the being as something at hand in the ordinary way, which thereafter comes to light and is challenged by the existence of the work as only presumptively a true being. Truth is never gathered from things at hand, never from the ordinary. Rather, the opening up of the open region, and the clearing of beings, happens only when the openness that makes its advent in thrownness is projected.”[iv]

It is obvious in Sia’s works that its attempts to open up the “open region” lies in her concealing of the region. Her works based on “found” paintings or the mutating of photos of serial killers or psychotic humans into works that either makes the objects beautified or acceptable disturbs the conscience – How much are they different from me?

Bringing the “work-being” into “movement and happening” is the task at hand for every artist. In her portraits and self-portraits, Sia seems to be breaking down the elements of image and form into movement and existing, mixing them with her need to mask them with a sense of dignity, whether they are emotional portraits of her mother, or of the tattooed people whose loneliness is depicted in their static standing or postured inscripted bodies coated by a desolate tinge of grey that projects our loneliness too. Nothing about them is redeeming except for the fact that they exist. Like Freud’s figures, the existing seems the only hope left.

The ‘light’ that comes with being “challenged by the existence of the work” comes from the Artist confronting the other – the canvas. In a sense, the relationship of the painter with the canvas besides assuming an ‘other’, is confronting the ‘other’ and squeezing Being out of it via the work. A tumultuous relationship that often yields non-work. And a lot of emotional stirrings that can only be resolved through the work. That conflict is very vital and yet painful.

The need to self-actualise the Truth is evident in Sia’s switch from still-life to portraitures and her haunting sketches and drawings of children or of actual existing people. The artist’s mind is fluctuating from memories sparked by old photos of strangers that in-turn spark the questioning of what happens when Being is erased by mortality. The conflict that comes when pure childhood is betrayed by the loneliness and the cruelness of a real, existing, dangerous world. Innocence struck by Truth’s cruel blow. Pain and suffering matched with a determination to see the purity and dignity of it all. Pain and suffering become a means of expressing the Dignity and Truth of Being.

In Sia’s work there is an alone-ness and an apart-ness that makes up for the power. We are “thrown” into the world, with no idea of the Lie and the Truth or Non-Lie. Do we scrape the barrel of Truth in the Art infinitely. Or do we still see the need of Hope in a Hopeless eternal quagmire that comes with existing. In Sia’s work, the answer is in the work. Where no answer can be the answer, as well as the depiction of No-Hope being the work. For it is the concealing and non-concealing that throws the Being into the Powerful Questionings that bring us closer to the realization of some truth, subject to our need to Question. Her further questioning is a further adding on to the further enriching of the Art. Long may it continue.

“Such reflection cannot force art and its coming-to-be. But this reflective knowledge is the preliminary and therefore indispensable preparation for the becoming of art. Only such knowledge prepares its space for art, their way for the creators, their location for the preserves.”[v]

[i] Martin Heidegger – “The Origin of the Work of Art” Basic Writings. Edited by David Farrell Krell. Harper Collins 1993 pg 177

[ii] Ibid pg 187

[iii] Ibid pg 188

[iv] Ibid pg 196

[v] Ibid pg 202

“A proposition is true by conforming to the unconcealed, to what is true. Propositional truth is always, and always exclusively, this correctness. The critical concepts of truth which, since Descartes, start out from truth as certainty, are merely variations of the definition of truth as correctness. The essence of truth which is familiar to us – correctness in representation – stands and falls with truth as unconcealment of beings.”[i]

If one stands in the gap of artistic questioning, the main question besides “what is true in Art?” would be “what is the truth in Art?” The storms of subjectivity flood such questionings, but more so, the complexities of Being. But what should always be apparent are the questionings, or the reflecting on these questions.

We often assume that Art conceals. We shun the obvious, disregard autobiographies, and proclaim that unmasking the masking is the key to great works of Art. What underlies Art is what makes the Truth deeper. We want gaps, not the obvious. We want “variations of the definition of truth of correctness.”

How important then, is the “unconcealment of Beings.” How should Art “unconceal?” These are age-old questions that will never be totally answered. Simply because human existence and the cosmos have always been more ‘projected’ and ‘concealed’ than ‘revealed’ to the world. This tension between concealment and unconcealment is, however, a very focal point of Artistic Truth.

In Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1573-1610) we see a classic example of that tension. The Saints and the Son of God are revealed in the magnitude. But the skepticism that is so prevalent beneath the revealing – the rebellious Christ, the cynical soldier, the truly vulnerable and confessional Apostle Peter in the midst of total despair. Caravaggio was unique, in that, he truly lived the Outside. As if he understood that standing on the fringes of the Outside was where the Truth was more illuminating.

Perhaps there’s a link.

“Truth establishes itself in the work. Truth essentially occurs only as the strife between clearing and concealing in the opposition of world and earth.”[ii]

What is this “strife?” What is to be ‘cleared’ or ‘concealed?’ In Caravaggio’s work, as in those of Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Eric Fischl, there is the strife between what one must strip to reveal and what one must conceal in order to provoke and reveal even deeper.

“Truth establishes itself in a being in such a way, indeed, that this being itself takes possession of the open region of truth. This occupying, however, can happen only if what is to be brought forth, the rift, entrusts itself to the self-secluding element that juts into the open region.”[iii]

“Self-secluding” is perhaps the most potent form of Truth-seeking in Art. The need to isolate, to avoid, and place oneself in a void of sometimes violent self-reflection is perhaps what binds the truth of the work to the viewer wanting the Truth in Art. Perhaps all we have are the experiences and the honesty that results in the work. Not to leave out the idealism and the courage to fail and to achieve the work.

In Sia Joo Hiang’s work, we are enthralled not just by the intensity of the work, but by the sheer exhaustive range of it. It is as though, different visual mediums are not enough to appease her restless search for what’s true. Her need to document her own personal “strife” and the “strife” of the work reveals to us the ultimate struggle of what to conceal and what not to. Or to totally expose a state of mind torn between chaos, complex peace and purity.

“…It says on one hand: art is the fixing in place of self-establishing truth in the figure. This happens in creation as the bringing forth of the unconcealment of beings. Setting-into-work, however, also means the bringing of work-being into movement and happening. This happens as preservation. Thus art is the creative preserving of truth in the work. Art then is a becoming and happening of truth. Does truth, then, arise out of nothing? It does indeed if by nothing we mean the sheer “not” of beings, and if we here think of the being as something at hand in the ordinary way, which thereafter comes to light and is challenged by the existence of the work as only presumptively a true being. Truth is never gathered from things at hand, never from the ordinary. Rather, the opening up of the open region, and the clearing of beings, happens only when the openness that makes its advent in thrownness is projected.”[iv]

It is obvious in Sia’s works that its attempts to open up the “open region” lies in her concealing of the region. Her works based on “found” paintings or the mutating of photos of serial killers or psychotic humans into works that either makes the objects beautified or acceptable disturbs the conscience – How much are they different from me?

Bringing the “work-being” into “movement and happening” is the task at hand for every artist. In her portraits and self-portraits, Sia seems to be breaking down the elements of image and form into movement and existing, mixing them with her need to mask them with a sense of dignity, whether they are emotional portraits of her mother, or of the tattooed people whose loneliness is depicted in their static standing or postured inscripted bodies coated by a desolate tinge of grey that projects our loneliness too. Nothing about them is redeeming except for the fact that they exist. Like Freud’s figures, the existing seems the only hope left.

The ‘light’ that comes with being “challenged by the existence of the work” comes from the Artist confronting the other – the canvas. In a sense, the relationship of the painter with the canvas besides assuming an ‘other’, is confronting the ‘other’ and squeezing Being out of it via the work. A tumultuous relationship that often yields non-work. And a lot of emotional stirrings that can only be resolved through the work. That conflict is very vital and yet painful.

The need to self-actualise the Truth is evident in Sia’s switch from still-life to portraitures and her haunting sketches and drawings of children or of actual existing people. The artist’s mind is fluctuating from memories sparked by old photos of strangers that in-turn spark the questioning of what happens when Being is erased by mortality. The conflict that comes when pure childhood is betrayed by the loneliness and the cruelness of a real, existing, dangerous world. Innocence struck by Truth’s cruel blow. Pain and suffering matched with a determination to see the purity and dignity of it all. Pain and suffering become a means of expressing the Dignity and Truth of Being.

In Sia’s work there is an alone-ness and an apart-ness that makes up for the power. We are “thrown” into the world, with no idea of the Lie and the Truth or Non-Lie. Do we scrape the barrel of Truth in the Art infinitely. Or do we still see the need of Hope in a Hopeless eternal quagmire that comes with existing. In Sia’s work, the answer is in the work. Where no answer can be the answer, as well as the depiction of No-Hope being the work. For it is the concealing and non-concealing that throws the Being into the Powerful Questionings that bring us closer to the realization of some truth, subject to our need to Question. Her further questioning is a further adding on to the further enriching of the Art. Long may it continue.

“Such reflection cannot force art and its coming-to-be. But this reflective knowledge is the preliminary and therefore indispensable preparation for the becoming of art. Only such knowledge prepares its space for art, their way for the creators, their location for the preserves.”[v]

[i] Martin Heidegger – “The Origin of the Work of Art” Basic Writings. Edited by David Farrell Krell. Harper Collins 1993 pg 177

[ii] Ibid pg 187

[iii] Ibid pg 188

[iv] Ibid pg 196

[v] Ibid pg 202

Other writings

- Artistic Individualism Defiled (Apr 96)

- Act on Impulse (Apr 96)

- Reflections from Pyongyang (May 98)

- The Culture, Truth & Lie about Jazz and Swing

- Authentically Inauthentic

- Review of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue (Oct 99)

note: this list does not show all of Kelvin's other writings. We are currently consolidating them. Cheers.

- Act on Impulse (Apr 96)

- Reflections from Pyongyang (May 98)

- The Culture, Truth & Lie about Jazz and Swing

- Authentically Inauthentic

- Review of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue (Oct 99)

note: this list does not show all of Kelvin's other writings. We are currently consolidating them. Cheers.

© 2013 KELVIN TAN